In the realm of medical research, a forgotten therapeutic modality is making a resounding comeback. Ultraviolet Blood Irradiation (UBI), an age-old technique that fell into obscurity, is now reemerging as a potential game-changer in healthcare.

The therapeutic potential of irradiating blood with ultrasonic waves has garnered attention as an effective treatment for viral infections, including the SARS-COV-2 (Coronavirus), HIV/AIDS, and Ebola virus. Despite sounding unconventional, this technique has existed since the 1990s, providing substantial aid to patients afflicted by these viral diseases.

During its initial days, ultraviolet blood irradiation held a reputation as a ‘miraculous therapy’, successfully combating various infections while concurrently bolstering the immune system of patients suffering from viral diseases. However, the advent of penicillin and other antibiotics marked a turning point, relegating blood irradiation to the annals of medical history.

Yet, as our world grapples with increasingly resistant infections, the utilization of ultrasound waves for blood irradiation could emerge as a viable option for treating such diseases.

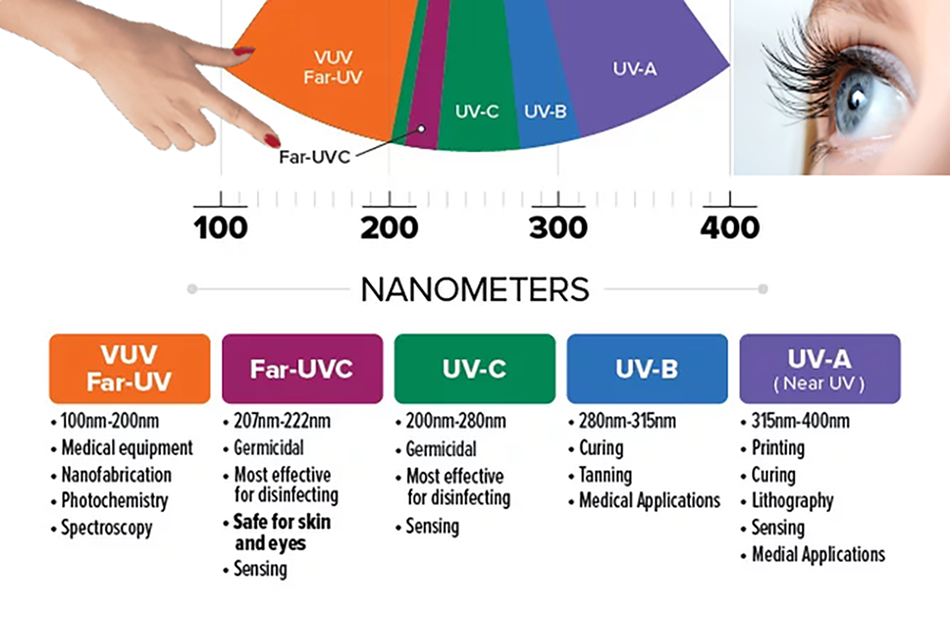

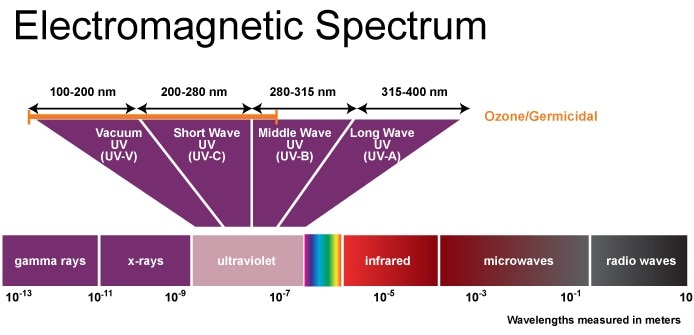

Dr. Michael Hamblin, Associate Professor, Dermatology, Harvard Medical School, states that in this context, the wavelength of ultraviolet light is of particular significance and is tailored for specific purposes. For instance, wavelengths ranging from 240 to 280 nm are employed for decontamination and disinfection, while wavelengths between 300 and 320 nm are utilized for phototherapy, targeting conditions like psoriasis and T-cell lymphoma.

However, when it comes to certain viruses, such as the SARS-COV-2 virus, ultraviolet light has been proposed as a tool to either inactivate airborne viral particles or impede their replication within the bloodstream. Ultraviolet blood irradiation was seen as an aid to enhance the body’s immune response, serving as an antiviral measure.

Various mechanisms have been postulated to explain the action of ultraviolet light on blood. However, it is established that only a small portion, approximately 5-7%, of the total blood volume in the body is sufficient to observe the effects of ultraviolet light. It is believed that this light intensifies the phagocytic activity of neutrophils and dendritic cells, oxidizes blood lipids, and inhibits the action of lymphocytes.

These effects prompted the proposal of utilizing ultraviolet light as a potential treatment option for multi-antibiotic-resistant bacteria and septicemia. The idea was to decrease hospital admissions and the mortality rate due to these conditions.

In the long term, the use of ultraviolet light is expected to supplant medication trials, which often yield adverse effects and other harmful consequences. Instead, ultraviolet light is anticipated to offer a non-invasive, safe, and more efficient means of achieving similar therapeutic outcomes within a shorter timeframe.

The resurgence of Ultraviolet Blood Irradiation (UBI) presents an exciting prospect for the future of medical interventions. With its potential to address a wide range of health conditions and stimulate the body’s innate healing mechanisms, UBI stands as a beacon of hope in the quest for effective treatments.

As further research and advancements unfold, the journey to fully uncover the potential of this forgotten cure continues, offering renewed possibilities for enhancing patient care and transforming the landscape of modern medicine.

References:

- Hamblin MR. Ultraviolet irradiation of blood:“the cure that time forgot”?. Ultraviolet Light in Human Health, Diseases and Environment. 2017:295-309.

- Boretti A, Banik B, Castelletto S. Use of ultraviolet blood irradiation against viral infections. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2021 Apr;60:259-70.

- Veleva BI, Caljouw MA, Muurman A, van der Steen JT, Chel VG, Numans ME, Poortvliet RK. The effect of ultraviolet irradiation compared to oral vitamin D supplementation on blood pressure of nursing home residents with dementia. BMC geriatrics. 2021 Dec;21:1-9.

Leave a Reply